The first time I saw Phil Hoff, he came to Windsor in 1961. He had just been away on a trip to Africa that had been arranged for him by President Kennedy, and he spoke to the Windsor Rotary Club.

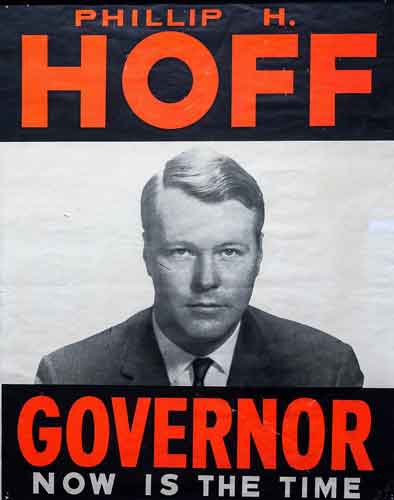

I was working as a rehabilitation worker for the State Alcoholic Rehabilitation Board. And I was in Windsor. There were three of us, or 4 of us, 4 or 5 of us actually, standing outside the Windsor fire station including the Fire Chief. Bill White was a probation officer, a good friend of mine; I worked with Bill a lot. And there were one or two others around, and all of a sudden we learned that Phil Hoff had been elected governor of Vermont, the first Democratic governor in 108 years. And despite the fact that I voted for him, and I think all of, or nearly all of the people there had voted for him, it was sort of a shock to your system. I mean the devil you know and the devil you don’t. And suddenly we had a new devil. And what was he going to do, and what did it mean to our jobs, and what did it mean to our community? Because I had never met Phil Hoff.

It was also a time, a year after John F. Kennedy had been elected president. So there was the Kennedy aura, the Kennedy mood upon the land. Kennedy was brilliant in his press conferences. He was funny. His use of words was magnificent, probably assisted strongly, I suppose, by Ted Sorensen. But, nonetheless, Kennedy was on his feet about as good as they get in my opinion.

And in addition we were a younger generation. We weren’t that far from the war. Many of us that I was associated with were brought up in the ‘30s and lived through the 2nd World War. We were all in that age when you sort of think things are possible anyway. And the atmosphere created by the President and by the media to some extent . . . . Television was beginning to come into its own.

And so for all that Vermont didn’t have at that time—and it was not the Vermont that you see today with pretty houses all over the landscape. It was falling down houses all over the landscape. And Vermont hadn’t begun to get its coat of paint in 1961 or 2.

Phil Hoff came on the scene, and the first thing he did, of course, was send the legislature home to see what it is we ought to do, which created this array of committees. I happened to be on one. And I remember rubbing shoulders with the Commissioner of Corrections at the time, and I thought, boy, he was a pretty exalted figure. And I was in Windsor, of course, and a lot of my work at that time was in the prison, working with guys there and taking them out into the community when they were paroled or released. And I was just a small part of all that.

In almost no area at all did we have enough people to do the kind of planning that needed to be done, for a lot of different . . . . whether you’re talking about economic development, the environment . . . . Hoff was big on the environment. But he did a lot of it through other people. He was a master with people, and he was the right man at the right time in that period.

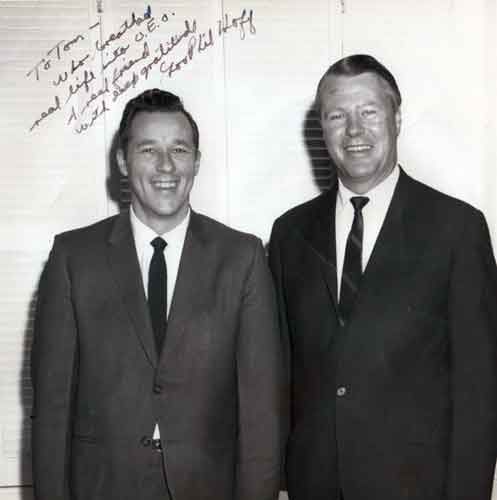

So I went in to see Hoff, and I talked to him. I liked him. He had a desk about the size of a ping-pong table, and on it were about 40 or 50 ashtrays. He smoked incessantly—probably give me the devil for saying all these things. We sat down and talked about the Poverty Program—what I thought we should do and could do and his willingness to participate and back the ideas that we generated. And I should put more emphasis on that than I have so far. And that is that if there’s any one single ingredient that I found in Phil Hoff that probably exceeds that of any other person I ever worked for was that when the chips were down, he would back you to the hilt.

I’m not saying that others that I’ve worked for haven’t. But that gave me a tremendous sense of willingness to talk to the press and raise these outrageous ideas that many people thought were outrageous anyway. So we established a good relationship.

I remember, one time we had an appropriation for Legal Aid—the first one, that had passed the House Appropriation Committee or was coming up in the House Appropriation Committee. I went to the meeting the night they were dealing with it, and they shot it down. And Hoff was furious. I called him up. I remember we had lunch in the back of the old Brown Derby. So I told him what had happened, and the House had not passed the bill. And he says, “My God, we’ll get the Bar Association in on this.” So he called his secretary, Priscilla LaPlante, at the time, and said, “Get the press in at 1:30.” This is 45 minutes lead time. About all he said to her. He didn’t even tell her what he was going to do or anyone else I guess. When the press came in, he went up one side and down the other for those guys not passing the Legal Aid program. The politics was in place. That’s the reality of the situation. But to be able to beat Phil Hoff on anything was of some importance to several of the Republicans on that committee, and, somehow or other, it did get shot down the night before. But with his willingness to go public immediately and criticize the Bar Association for not doing more . . . . I mean, he was a member of the Bar. He had no fear of offending. Some might say went too far sometimes, but he said what he really thought. And the public liked it. The press loved him.

Phil Hoff was not in there for the fun. Phil Hoff was probably the strongest-minded politician I ever met, who established broad ideals and was perhaps more willing to lose for those ideals than anyone else I ever knew. Because in politics, Hoff said, you don’t amount to anything if you aren’t willing to lose for it. If everything is up for sale, there’s no principles involved. So you’ve got to have things you are willing to lose for. And I think I learned that from Phil Hoff. He would take a stand and didn’t always have to put his finger in the wind to find out how the public was thinking. Politicians today read the polls before they read the paper it seems, many of them. And the idea of standing for something and not changing when the wind changes is very unusual.

Bernie Sanders’s success, in my mind, in Vermont is due in part to his—what he’s saying, but it may be more to the fact that he has the same message he had 40 years ago, and he hasn’t changed it a bit. He combs his hair and wears a tie once in a while now, but I— you can’t fault a guy for that.

I can remember my father giving his State of the State speeches, in which he proposed a sales tax. No tax makes you very popular, and leave it to my father to go ahead and say he was going to do it, and he did. Phil Hoff walked right up to him. Said, “I think you’re right, Governor. I’ll support you all the way.” Hoff did what he thought was the right thing. And he wasn’t afraid to lose.

Under Hoff, we saw the reformation of welfare in Vermont. Is it perfect? Hell no, but it’s a lot better than it was then. And we were able to see some things happen. We saw Legal Aid happen. We saw Family Planning programs become statewide. We saw huge increase in the commitment of the state to daycare.

Hoff ran for U.S. Senate in 1972, I think. The timing was bad. Planning for the campaign was poor, I thought. Hoff worked hard, but he didn’t get anywhere on that. But as I say, he wasn’t afraid to lose. He would go out there and lose if he had to. He’s always stayed connected to politics, as I’ve known him. He went back into the State Senate. As a senator, the only governor that I know who has ever done that. Maybe others have, but he worked as a state senator.

I mean, he’s everything you want in a politician. He was sort of like building from the flame that Kennedy lit by being elected in 1960. And you had two young, personable, charming, good-looking men with good-looking wives saying, we need to go somewhere. They said it in Vermont and they said it, in fact, in New England as a whole, with the possible exception of New Hampshire. There was Ken Curtis in Main who showed leadership, and there was some Republican leadership in Massachusetts, for which there was some of that same sense of mission for this part of the country.

Republicans and Democrats really liked Hoff. They wished he wouldn’t do some of the things he did, but they really liked him. Today politics doesn’t have anything to do with like. It’s what’s in the next news cycle unfortunately.