Salmon had taken over. My father had handed him the key to the office, I suppose. And I was shortly thereafter named Secretary of Human Services, a job for which many Republicans thought I was too liberal. So I had to go through confirmation hearings, particularly in the Senate, and John Howland was one of my champions. Another one was Russ Niquette, who was a Democrat from Winooski–prominent, longtime Democrat. There were some hard right people on that committee.

The rumor started to circulate that they were going to ask me some personal questions. One of the members of the press told me this. It had to do with the fact was I or was I not an alcoholic. And I am a recovering alcoholic, and I make no bones about it. At that time, I don’t know how many years, but probably 10 years or 15 or something. I don’t know. They never brought up the question. I survived the committee vote somehow and survived the final vote.

But when I think of the cadre of Republicans that I dealt with in that 4 years in the legislature, I can’t find an equivalent 4, 5 people today, possibly on either side of the aisle. The level of cooperation between people, agencies, the interaction, is much more tense. There’s less sense of collegiality. When Hoff was governor, and even when my father was governor, there was a sense of mission around certain subject areas—the environment, for example, the bottle law, things like that. And people worked together, even if they weren’t 100 percent on every issue, and they worked together and got things done.

Today we put people in cubicles and put a screen in front of them, and they don’t talk to each other. They talk to the machine. And I personally feel a lot more communication occurs when people can speak to people directly as opposed to through electronic media. In fact, I think you lose at least half if you don’t have the personal, if you don’t see the body language, so to speak. I’m not an expert on the subject, but if I have to convince somebody of something, or if I have a squabble over something I buy, I don’t want to talk about it on the phone. I want to go see them.

Emory Hebard–considered by everybody to be quite conservative. I convinced Emory Hebard. I said, “Look, Emory, you put $100 down, the feds will give you 200. The $300 will pay putting it through the system. The federal money will pay for you getting the hundred dollars. He didn’t have any tr. . . . . He was a PhD from Middlebury anyway. He didn’t have any trouble understanding that, and he was my great ally, and everything I wanted to do regarding federal money he supported, the flexibility I needed. So I had him. I had John Wackerman, who nominally was still a Republican, and he was, of course, Commissioner of Welfare. So there was a lot of things we were able to do and loosen up.

Home Health began to draw money down as a result of being able to match federal funds. And that was a major achievement which has never been particularly noted. But there were other wonderful people. There was Edgar Janeway, who had been a longtime Republican committeeman from the southern part of the state, a man you’d trust your life with. Bob Gannon from, from Springfield. Because many of the Republicans’ premier issue or an issue of which they would stand upon was matters of the environment, which means government intervention any way you slice it. Peanut Kennedy. I could work with Kennedy. In fact I sold cars for years before on the side working for Peanut.

The the issue wasn’t, “Is there a problem?” Everybody knew there was a problem. The question was, “Which problem and how much?” The problem today is: “Well even if there’s a problem the government shouldn’t get into. They’ll just screw it up.”

As I say, I was Secretary of Human Services under Tom Salmon. I felt I did a pretty good job. I was the second one. The first one was only a year there under my father when he was governor, guy by the name of Bill Coles. And not much had changed in that year. Nobody really had a clear vision of what they wanted the agency to do. And let me be clear: I didn’t have a clear idea of what the agency should do either when I went in. But I was young enough and ambitious enough to believe that I would find things in ways that would begin to do the job.

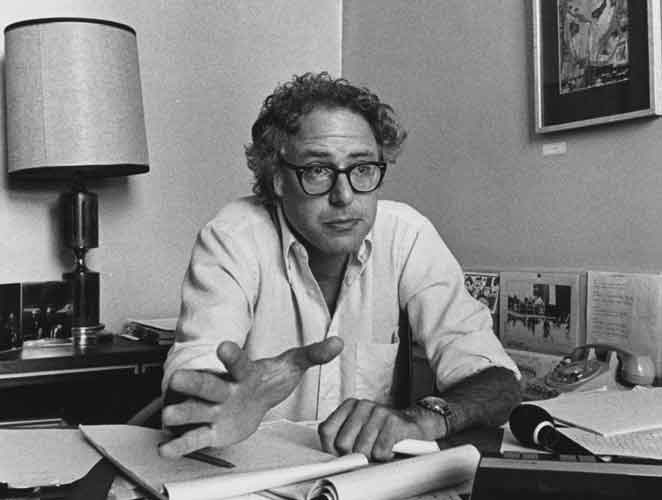

I don’t know whether I was too young, but I was certainly too liberal for what some people were looking for. Others probably thought I wasn’t liberal enough. I can remember sitting across the table from Bernie Sanders arguing about food stamps and trying to defend the status quo. And Bernie was wanting more and more. And Bernie was right. And I knew in my heart he was right, and there wasn’t a thing I could do about it. I’ll never forget that.

I learned a couple of things, by having come from where I came from. I had worked down in Springfield and Windsor and Windsor County. I knew people throughout the mental health system. I got involved in some of the early development of that. And, of course, I was involved in all the anti-poverty programs—the Legal Services program, the statewide Family Planning program, programs of that sort. One way or another I always had my finger in there. And was able to select good people to work for me. I always figure that was always my ace in the hole that I had people around me smarter than I was.

But the other thing that I learned by having come from the field is that the Montpelier types didn’t have clue about what was going on out there, didn’t have the feel of it. What I’ve been thinking about is the failure of all of the professions really, and government in particular, to find a way to assign some aspect of generalist functions to human services workers.

One time I was head of what was known as the New England Services Human Coalition, most of us who had come from the Poverty Program at the time. And we used to meet once every couple of months or so. My thing was always that unless you have generalist skills, you’re not going to survive, or at least you’re not going to get very much done.

And then complicating this whole subject was the invention of the computer, which managed to take up an awful lot of time filling out forms that nobody reads. We did keep data even before the computer. But I was there only a year as a counselor before I realized that when my paperwork was in shape, I wasn’t working very hard. And when I was working really hard, my paperwork was not in shape. But within the bureaucracy, it’s understood that you’re good if your paperwork’s in shape. Never mind the what you’re doing, because they don’t understand what you’re doing anyway.

I think one idea, which I never did anything about, would be to take about 50 percent of the people in Montpelier, in the human service bureaucracy, and put them in the field, and take 50 percent of the people in the field and put them in Montpelier. You should and could do the same thing in education. Take educators out of the high schools and grade schools. Put them in related offices–mental health offices and . . . . I mean, the specifics would be very complicated, be very hard to do this, if not impossible. Probably impossible. But the failure to understand across disciplines the opportunities that are there. . . . And the case finding–the early intervention that could occur .

For a whole lot of reasons, I’ve had kind of crazy experiences with rich and poor, well to-do and not so. I’ve had the luxury of being with very bright people, most of them brighter than I, certainly, and, and yet, at the same time, have an understanding of those who don’t have, have had the background in education, and IQ that can take them anywhere.

It taught me that the things that you really learn don’t come out of a book or a manual, God knows, of a “how to do it.” You have to learn how to reach around the bureaucracy and get back to either the people that need help or the few workers in the field who aren’t part of the official chain of command. They just do the work.