In 1963, on November 23, I was in the parking lot of a small supermarket across from the Windsor post office right next to the Windsor House. And it came over the radio. I probably was listening to the radio in the car. I had 2, 3 kids with me. And Kennedy was gone. I had to go in and get my wife to get her groceries and get out of the store and go home, which is what we did, and turned on the television, which conveyed everything that went on. I witnessed the Oswald assassination on TV at the same time.

In those days I read both Newsweek and Time magazine. I don’t know how I had time to do all that, but I did. And then they were announcing suddenly the Poverty Program. And I was in Windsor, of course. And a lot of my work at that time was in the prison, working with guys there and taking them out into the community when they were paroled or released. And I probably learned more on that job about government, about people, about people who cared, and people who didn’t care. And I learned perhaps most about myself by working with other people.

Then I met the warden of the prison. He was a great guy. And he was so unlike the stereotype of correctional officials of the last 15 or 20 or 25 years, for he was strictly oriented to helping people.

So, anyway, suddenly they announced this Poverty Program. Nobody knew exactly what it was. Newsweek said it’s doomed to fail. And it was minimal amounts of money put into what was the community action part of the program, which is where I became first involved. The program was put together with the usual agreements between different special interests, although the special interests in this case were generally of a more positive nature. Organized labor wanted programs like the Job Corps. And there was a Job Corps, and it was in some cases successful, in some cases not. They made a lot of mistakes in the beginning about locating them, about the kind of training people ought to have who were going to manage and run the programs.

There was no clear track on how you did all this stuff. There were at least three operating philosophies for what community action was supposed to do. And they did not necessarily complement one another. Some people felt community action means getting things done through the system, cooperating, community development, that kind of thing. Others saw community action as the poor becoming organized and asserting themselves and leading their own way. And even within Vermont in the five Community Action programs we had, the differences would vary from a program to program.

I became the first president of Windsor Community Action, and then all of a sudden we were told that we had to merge with Windham County. Well this required my imaginary political skills. And I ended up president of what later became Southeastern Vermont Community Action or SEVCA, a name that it still has. And that was in 1966, I think.

The Vermont legislature scarcely noticed when this Poverty Program began. Certainly selected members picked it out, but by and large it wasn’t seen as something big enough to worry about. I’ve always felt that you could start a federal program in Vermont . . . . You can do almost anything you want for two years before anybody notices. And in some respects, that was true in the case of the Poverty Program because it was a very controversial philosophy underlying it: the conflict between those who felt what we were trying to do was learn how to work together; others felt confrontation was necessary.

The big thing in those days was: involve the poor. That was the message up here: involve the poor. How you involve the poor, whether you do it in a controversial or a collegial way. That was a continuing debate throughout the whole history of the program. In other words, were we always to be adversarial, or could we find things to work together on.

And of course, there was always tension between the federal government and the local agencies as to who should be on the board and who shouldn’t be on the board. At least a third of the people on your board had to meet income insufficiency levels. But we did identify people who later became leaders, mostly women, as a result of the Poverty Program.

I remember as I do about every job I’ve ever had: I go in and sit down in the chair, and I say, “Well, I wonder what a director of a community action program is supposed to do?” And I always think of that because I think every job I’ve ever had, I’ve always–other than when I helped on the truck at Montgomery Wards–I think I always sat down and said, “I got a nice title, but I don’t know what I’m supposed to do, and there isn’t anybody around here any smarter than I am to tell me what to do.” So I found my way that way in most things that I did.

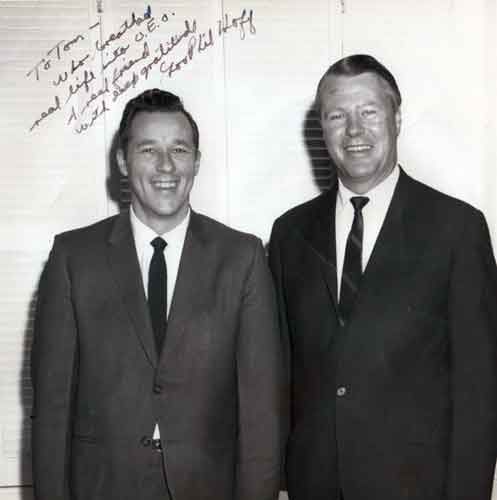

I’d had some help and met some people from Montpelier in the process. And Paul Guare from Montpelier was an ex-newspaperman. He’d been a Hoff confidant and was a genuinely great good guy, a helpful guy to Hoff. But when Hoff appointed him on some sort of temporary basis as director of the program it seemed to conflict in the minds of many with his job as head of Rural Development. And the newspapers made a fuss out of that, and probably about whether he was collecting money from two places and all that. At any rate, he wanted to get out of it. So I went to Montpelier and advocated for the director of the program in Montpelier, a guy by the name of Jerry Goldman. And Tom Kenny was one of Hoff’s assistants. The other was, at that time, was Ben Collins.

I was advocating for Jerry, and I remember Tom Kenny said, “What about you? Aren’t you interested in the top job?”

I said, “Well no.” I hadn’t thought about it. I said, “I haven’t got a Master’s degree.” I felt at that time that the key to the kingdom was a Master’s degree. And I had taken trips to Boston trying to see if I can figure out some way to get a Master’s degree through Boston University at that time. But I never even talked to the right person, I don’t believe, in that regard. He said, “Well, why don’t you meet with the governor and see?”

I got a phone call a few days later, and it said, “Will you come up and meet with the governor?”

I said, “Sure.”

I didn’t know Phil Hoff. I mean, I’d met him, but I really didn’t know him at all. He had a table at least eight feet long, covered with papers and several ashtrays, some of them with smoking cigarettes in them and some with not. And we sat down and talked. He sat at the corner of the table and talked about what the Poverty Program might do, what kind of money we could bring into the state, what we might want to do with it. But we talked pretty generally, and he says, “Do you want this job?”

And I said, “Well, yeah. I think we can do some things with it.” I don’t recall whether I gave him my litmus list of all the things that I thought could be done. I always had a lot of things I wanted to do, from daycare . . . . And of course, Head Start was a priority at the federal level. Vermont did a lot of good early work in Head Start, not because of me but because of a lot of good people out in the communities.

“Sure, I might be into it.”

“Well,” he says. “I tell you what. You want the job . . . . I don’t know why you want the job, but if you want it, you can have it.” And that was how I was hired to head the Poverty Program.

And I can remember walking in, as I have at other jobs, I walked in the office and, of course, I was in the room with the best window and the biggest desk. I remember sitting in the chair looking out the window and says, “I wonder what the head of the Poverty Program is supposed to do.”

I was a true believer. I thought everything was possible. I thought programs would work. I thought everybody was honorable, mostly. And most of the ones we had in Vermont were.